When the nation’s highest court considered his first case In the Rastafari case this week, none of the Supreme Court judges or lawyers involved mentioned the minority faith, much less raised its tenets or the sacred importance of dreadlocks.

Still, for devout Rastafarians the historic legal battle over protecting religious freedom behind bars was a milestone that many in the community said highlights a long history of discrimination and alleged lack of accountability.

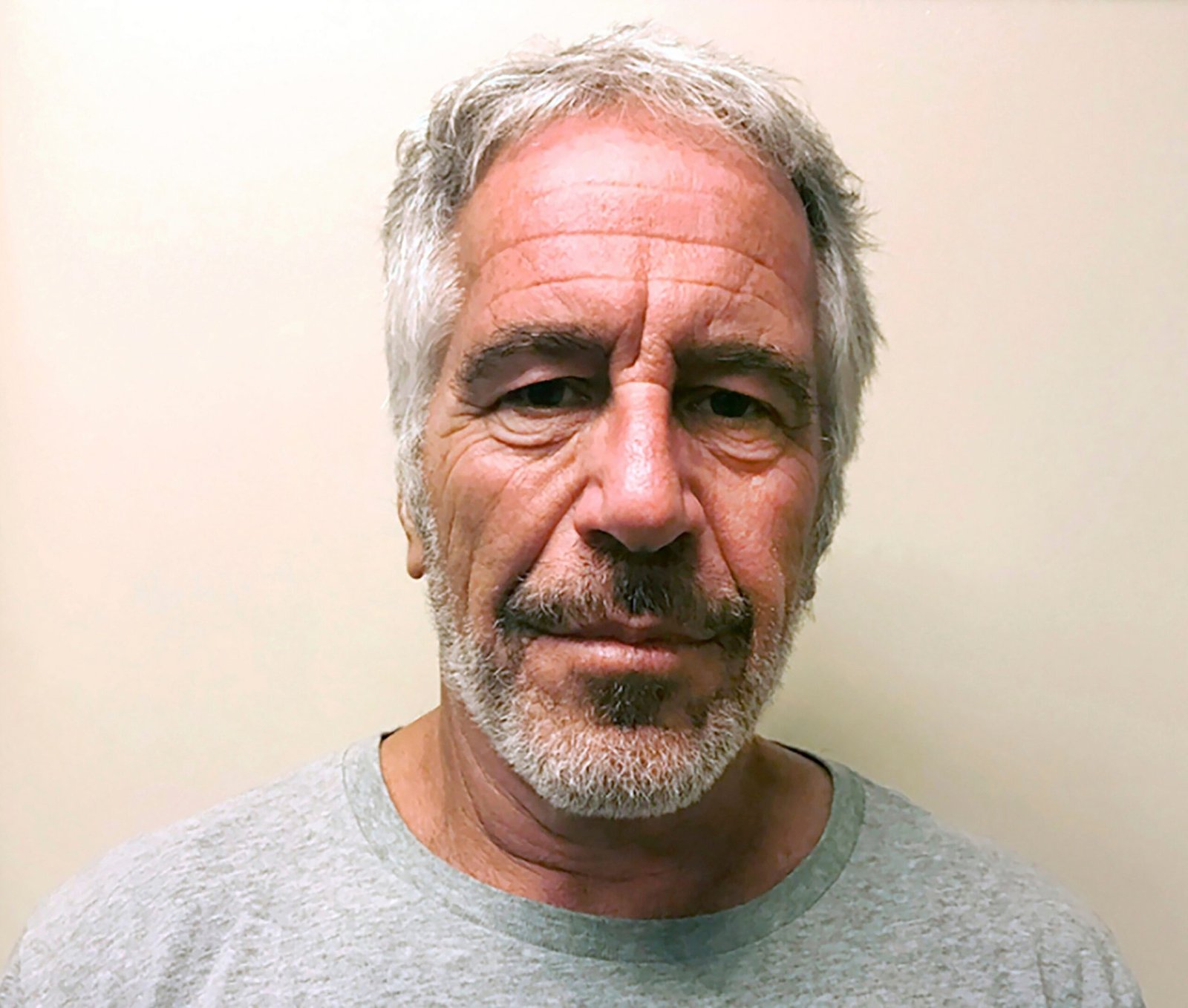

At the center of the case is Damon Landor of Louisiana, a self-described devout Rastafarian who had left his hair uncut for nearly 20 years as part of a pledge of his faith known as the Nazarite vow.

Damon Landor’s dreadlocks had been growing for 20 years when he was incarcerated in a Louisiana state prison to serve a five-month sentence for a drug crime.

US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

The Rastafarian religion, originating in Jamaica in the 1930s, recognizes an Ethiopian messiah and teachings of justice, righteousness and natural living. Dreadlocks are the most physical manifestation of a rasta’s beliefs.

“It’s like a sacred pact that the Rasta man made with the almighty,” said Ziah Ayubu, a devout Rastafarian and reggae artist from Silver Spring, Maryland, who is closely following the Landor case. “I see [dreadlocks] like my spiritual antennas.”

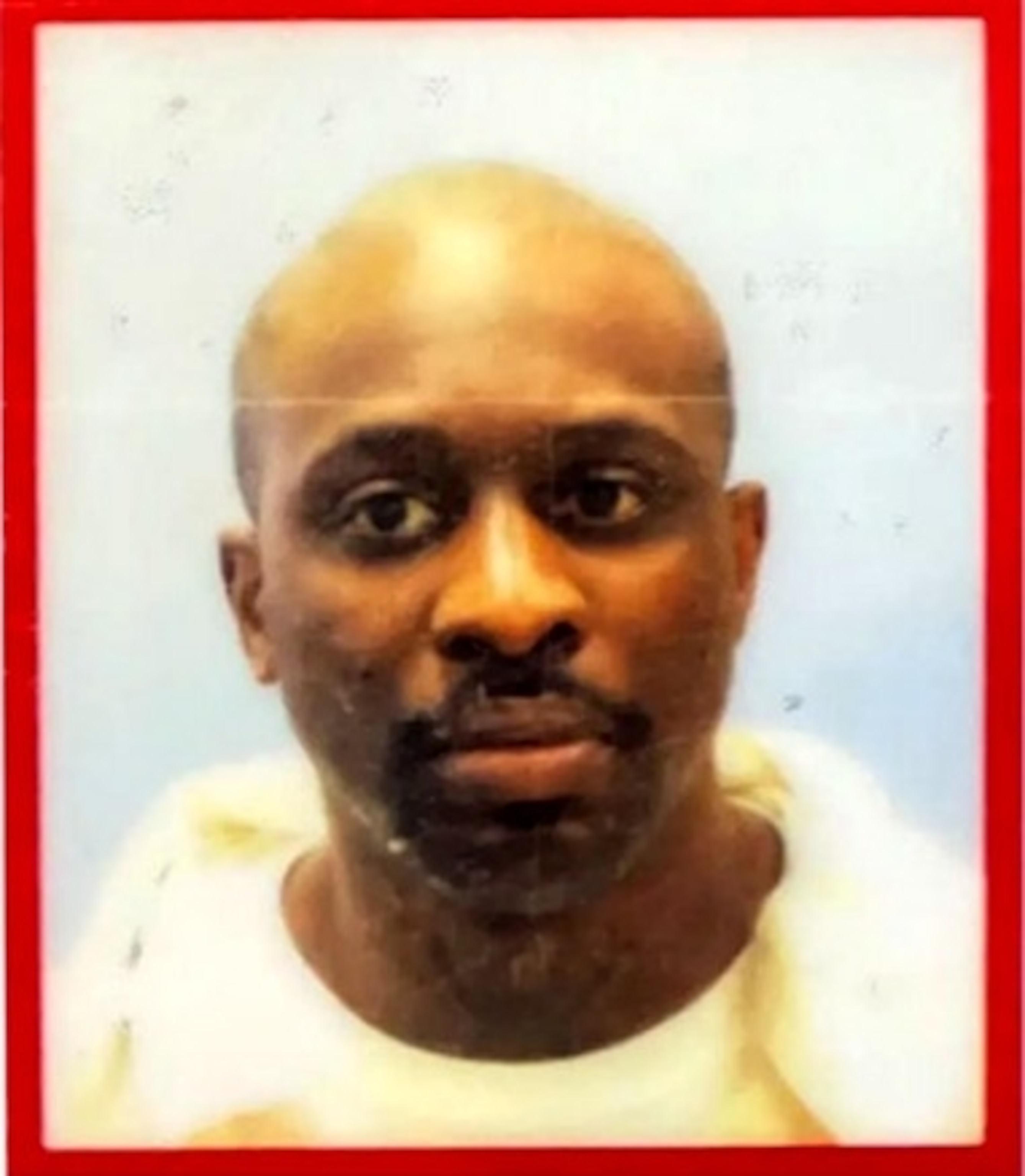

When Landor arrived at the Raymond Laborde Correctional Center to serve the final three weeks of a five-month sentence in 2023, then-Warden Marcus Myers and state corrections officials they allegedly handcuffed him to a chair and forcibly shaved him.

Damon Landor claims he was forcibly shaved by Louisiana prison guards despite his claims of a Rastafarian religious exemption to keep his dreadlocks.

US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

His request for a religious exemption to keep his dreadlocks was dismissed out of hand. Landor later attempted to sue for an alleged violation of his religious rights, but a federal court dismissed the claims for damages.

“When they tied me up and shaved me, I felt like I had been raped,” Landor said in a statement to ABC. “And the guards just didn’t care. They would treat you anyway. They knew they shouldn’t cut my hair, but they did it anyway. That’s what they do. They were just using their authority.”

Marcus Myers was warden of the Raymond Laborde Correctional Center when Damon Landor was imprisoned.

Louisiana Department of Public Safety and Corrections/Facebook

In 2000, Congress enacted the Religious Land Use Law and Imprisoned Persons Explicitly require states with federally funded prisons to allow sincere religious practices, such as a Rastafarian’s dreadlocks, unless they can demonstrate a “compelling state interest.”

But there has been no legal consensus on whether a prisoner whose rights were allegedly violated under the law can sue individual prison officials for damages in federal court. The United States Supreme Court is ready to clarify it.

“The law requires correctional officers to respect the religious practices of incarcerated people. But without harm, the law has no force,” said Landor’s attorney, Zach Tripp. “It is a right that has no remedy, and prison officials can ignore it with impunity. Without harm, there is no responsibility.”

Louisiana Attorney General Liz Murrill maintains that state prison officials should not be subject to lawsuits seeking damages for alleged violations of the Religious Land Use and Incarcerated Persons Act.

ABC News

Louisiana maintains that state prison officers have immunity no matter what.

“We support the principles behind the protection of religious freedom and the laws that have been enacted by both Congress and our state,” Louisiana Attorney General Liz Murrill told ABC News. “But in the prison environment this becomes much more complicated. If in a situation like this we suffered damages, the entire state budget could be ruined.”

Civil rights advocates and other alleged victims of discrimination against Rastafarians say there is an urgent need for the Supreme Court to give victims of religious discrimination a clear path to monetary responsibility.

“I just wish no one had to go through what I went through,” said Solomon Tafari, a Virginia man who spent a decade in solitary confinement in a state prison because he refused to cut his dreadlocks. The state’s prisoner grooming policy offered no exceptions for Rastafarians.

Dreadlocks are considered a physical manifestation of a devout Rastafarian’s commitment to God.

ABC News

“Being isolated, you go out maybe two or three times a week. They put you in a dog cage and they call that recreation,” Tafari told ABC News.

Tafari, who was released in 2014, attempted to sue for damages under federal law, but got nowhere.

“There were times when I was in deep depression, I thought about committing suicide, that aspect was there too. But it’s my faith that kept me going,” he said.

In 2018, Thomas Walker, a Rastafarian in an Illinois state prison, was forced to cut off his dreadlocks for what officials claimed were security reasons. The same thing happened to Carlos Thurman in Kentucky in 2022, despite his request for a Rastafarian exemption. Later the State changed its policy and solved the case.

Corey Shapiro, legal director of the ACLU of Kentucky, sued state prison officials in 2022 for alleged religious freedom violations after forcibly cutting off a Rastafarian inmate’s dreadlocks.

ABC News

“Justice is compensating him to some extent in the form of compensatory damages and in the form of money,” said Thurman’s attorney, Corey Shapiro, legal director of the ACLU of Kentucky. “Money is also a deterrent, right? Like the Department of Corrections would think twice if they knew they were going to have to pay money to someone.”

Nearly 600 complaints related to multiple forms of religious practice were filed in select federal prisons between 2017 and 2023, according to to 2025 reportt of the United States Commission on Civil Rights. But only one of them had a favorable result for the prisoner; which advocates say is further evidence of limited respect for religious freedom behind bars.

Charles Price, professor of anthropology at the University of North Carolina, specializes in Rastafarian history and culture.

ABC News

There is no monetary sum that can repair the damage caused by forcibly shaving dreadlocks from someone’s head,” said Charles Price, a Rastafarian academic at the University of North Carolina. “But at the same time, what kinds of things does the system do to recognize its mistakes? One of the things you do to recognize grievances is pay reparations or pay damages.”

Ayubu and members of his band, Proverbs, are praying that the Supreme Court case will help change the way society views Rastafarians and their sacred hair.

“Growing up in the ’70s and ’80s, you know, if you were put in jail, you could guarantee your hair would be cut,” he said. “It’s 2025, I thought all that was over.”

Reggae artist Bob Marley helped make Rastafarian beliefs and culture mainstream in the 1970s.

ABC News

He said the community of believers, estimated to number several hundred thousand in the United States, hopes the judges will bring about change.

“We are still here, we are still working, we still love each other and we live together,” Ayubu said.

Ziah Ayubu from Silver Spring, Maryland, is a devout Rastafarian and founder of the reggae band Proverbs.

ABC News

The high court is expected to decide whether federal law allows individual lawsuits for damages against prison officials for alleged violations of religious rights by the end of June 2026.